- CASA-1000 will allow Tajikistan and the Kyrgyz Republic to export surplus hydropower to Pakistan and Afghanistan.

- The project serves as a model for regions seeking to create large-scale, cross-border power grids benefiting from a combination of multilateral financing and private sector expertise.

- Development banks, donors, private contractors, and governments worked with the World Bank Group for almost two decades to turn an audacious idea into reality.

By Gayle Young

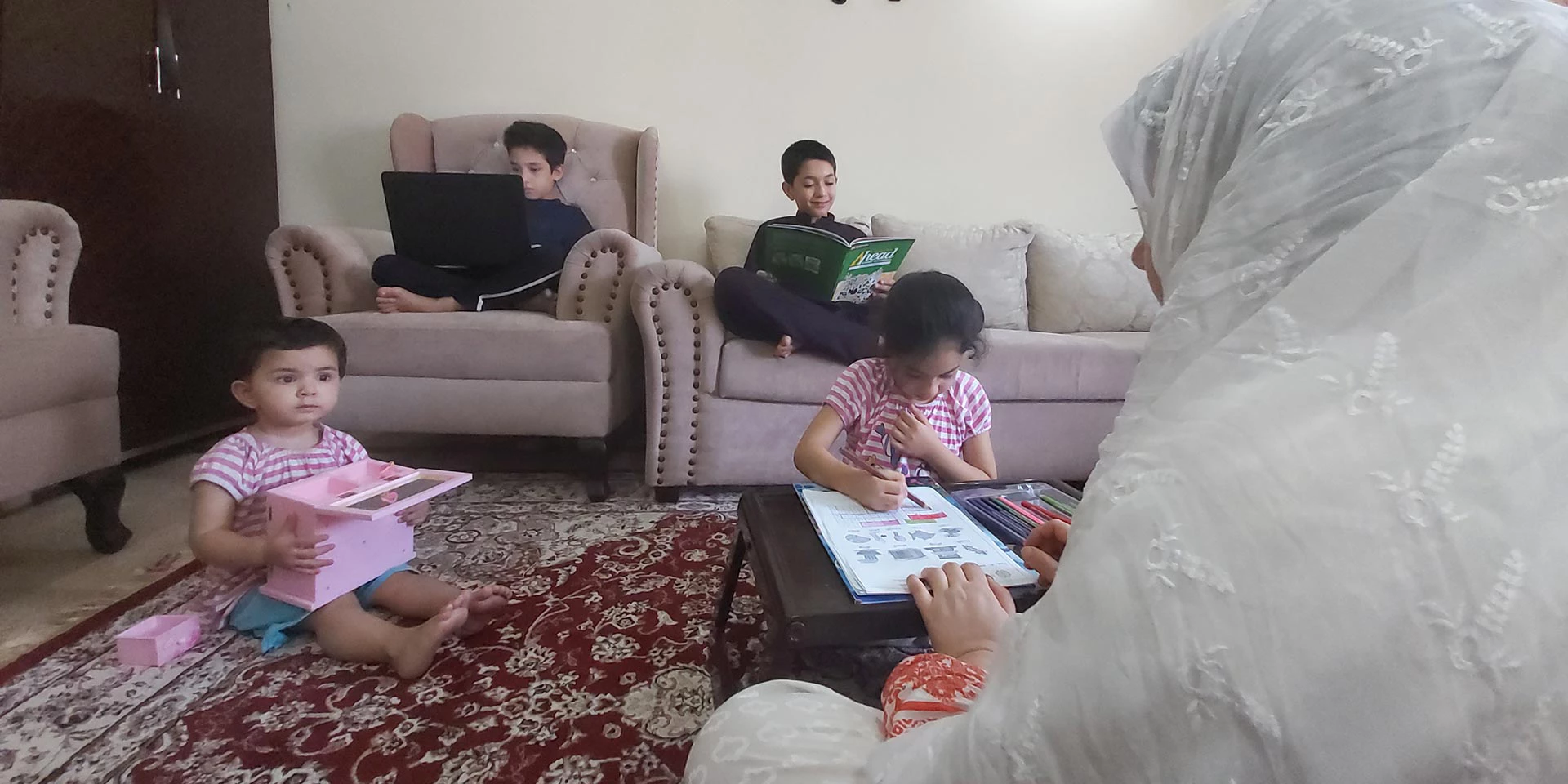

In many ways, the massive electrical highway that connects power grids across four low-income countries comes down to improving the lives of individuals, like Saira Ayub’s children who need reliable power to keep up with their online classes.

The mother of four in northern Pakistan struggles with summertime power outages that have made remote learning for her children even more difficult. “With more reliable electricity, I hope we will be able to plan our work,” she says.

Ayub is not alone. During the summer millions of people in Pakistan and neighboring Afghanistan suffer from frequent power outages that hinder learning, disrupt businesses, and even endanger health and safety. At the exact same time of year, some 1,400 kilometers to the North, torrents of melting snow from the Pamir mountains creates a surplus of electricity generated by hydroelectric power plants in the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan.

Young women learn computer skills in Pakistan, will benefit from a steady stream of electricity during summer months. © Visual News Associates / World Bank

The Central Asia-South Asia Regional Electricity and Trade Project, known as CASA-1000, aims to use this seasonal surplus of electricity in Central Asia to alleviate the shortfall of electricity in South Asia. Currently under construction, the project will soon allow Tajikistan and the Kyrgyz Republic to export more than 1,300 MW of seasonal hydropower to Pakistan and Afghanistan by linking the electrical grids of all four nations. Private contractors are building two new convertor stations and more than 1,350 kilometers of new transmissions lines that cross borders and remote landscapes to link up the four existing power grids.

“With better management of power supply, we will be able to boost the local and countrywide economy,” says Mr. Atif Jawad, Commercial Manager for Peshawar Electric Supply Company (PESCO) in Pakistan.

It is estimated the total project will cost US$1.2 billion, with the World Bank providing over half a billion in grant and credit financing. In addition to providing financing, the World Bank worked with the governments on the enabling regulatory framework and supporting projects to improve livelihoods in the communities along the corridor, which will receive a share of projected revenues when the project starts operations. Once the extended grid is up and running, other neighboring countries may potentially be able to buy or sell surplus energy as well. It is expected that the CASA-1000 infrastructure will lead to more clean energy exchanges between the countries.

“The project represents one of the first substantial economic ties between Central Asia and South Asia,” says Cassandra Colbert, IFC Regional Manager for Central Asia. “In addition to addressing electricity shortages in the South Asia countries, it will also ensure a steady source of revenue for the Central Asia nations.”

The idea for a linked grid was first proposed by the World Bank in 2006 but instability in the region, combined with the scope of the project, meant years of international negotiations to craft a feasible engineering plan and secure financing from development banks and donors.

To facilitate the decision-making process, the four countries established an Almaty-based secretariat tasked with agreeing on costs, rates, and procedures. Donor support was brought together from the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund; the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development; the European Investment Bank; the Islamic Development Bank; the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office; the United States Government; and the World Bank - along with other bilateral donors channeled through a Multi-Donor Trust Fund.

Given the difficulties in attracting private capital to such a complex project spanning across four different countries, IFC’s structuring of contracts to build the new transmission infrastructure had to be innovative to attract the right kind of private partners. To ensure viability and timely delivery of all components, the Project was divided into ten contracts that were each competitively tendered and financed by the international financial institutions (IFIs). The last of the ten tenders was completed in 2020 and electricity is slated to start flowing before the end of 2024.

“The structuring has been enormously complex,” said Martin Sobek, IFC Senior Investment Officer. “But it can serve as a template for other areas of the world seeking to build ambitious large-scale public-private partnerships that can improve trade and spur economic development across regions.”

While it is hoped that CASA-1000 will boost continued regional trade and cooperation, the project will perhaps, in the end, have its greatest impact on the small communities and businesses that will benefit from a more stable electricity supply.

Asgar Baloch, a social worker in Pakistan’s heavily populated South Punjab, says routine blackouts and brownouts force smallholder farms and commercial businesses to shut down in the crippling heat of summer. “I know people, including my friends, who have lost their jobs,” he says. “With reliable electricity our lives will get better, farmers will have more output and hospitals will provide better treatment to patients.”

Published in March 2021