By Daisy Serem

NAIROBI—For as long as I can remember, my youngest sister, Edith Serem, has always wanted to be a doctor. It all started when she was six years old and had to undergo an appendectomy, spending several days recovering in a hospital in Nairobi, our hometown. She watched with intrigue as the doctors in the pediatric ward cared for their young patients—and in that moment, she knew that this is what she wanted to do.

"I was always happy being in a hospital," she recalled. "I remember after my surgery, I had to go for follow ups with the pediatric surgeon. We would have such good conversations and he would teach me so many interesting things. I just remember thinking, ‘I also want to do this.’"

When she entered medical school in 2007 at age 18, I watched her endure many long nights and busy days as she studied for some of the toughest exams. To me, the life of a med student seemed brutal. But Edith, who is now a 31-year-old medical resident, formed a community of fellow doctors, some of the brightest minds in Kenya, who cheered each other on through the highs and lows. Through my sister, I got to know some of them, and we have stayed in touch. These days, they are on the frontline of the coronavirus pandemic, working in different health facilities across Kenya to ensure everyone has a fighting chance against COVID-19.

Daisy Serem, Communications Officer at IFC. Photo: Courtesy of the author

I recently reached out to them to get more intimate and personal insights of the way COVID-19 is affecting my country. In the process, I learned about the critical role of private health providers during the pandemic. Statistics are easy to find—the Kenyan government has reported more than 101,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19, with 1,766 deaths, as of the beginning of February—but I wanted to delve deeper into what people there are experiencing, and how life has changed.

Young doctors on the frontline

Mellany Murgor, a 29-year-old doctor, is one of the people I checked in with. The last time I saw her was at my sister’s wedding in December of 2019. There was no hint of a virus in Kenya then. We danced the night away, mask-free, celebrating the new couple. She had been working as a Medical Officer at Nairobi Hospital, one of Kenya’s leading private hospitals, for just a few weeks at that point. But just a couple of short months later, the pandemic crept into Kenya, and she was assigned to a newly created COVID-19 unit.

It was the toughest time of her career, she said. There were only a few personnel working in this unit, and many were fearful of being assigned there. The long hours in the COVID-19 unit, fighting a relentless virus, threatened to break Murgor and her colleagues.

“The numbers at some point became too much, it was almost overwhelming even in our facilities,” she told me. “Also seeing the suffering and not being able to do much beyond what has been recommended has been the greatest challenge.”

Mellany Murgor, a doctor at Nairobi Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya.

Photo by: Kennedy Otieno Oloo/IFC

As the pandemic spiraled, Nairobi Hospital put in place measures to not only serve their patients, but also ensure that staff are well taken care of. This included providing adequate personal protective equipment, hiring more health workers to reduce the workload, and offering counseling services to improve their mental well-being.

“We were also provided adequate rest time,” Murgor said. “For instance, we could not work for more than three days, we needed to rest from the COVID-19 unit.”

Private health-care facilities like Nairobi Hospital, where Murgor works, are helping the government to flatten the curve and meet the soaring demand for health care. Murgor told me that for medical workers like her, the pandemic has exposed the vast inequalities in accessing quality health care.

Sylvia Gendo, 29, another of my sister’s peers, described to me what inequality actually looks like. Gendo is a doctor in charge of the COVID-19 and the intensive care unit at Machakos County Referral Hospital, a government facility in southeastern Kenya. This hospital serves more than 1.4 million people living in and around Machakos, about 40 miles southeast of Nairobi, as well as referral cases from nearby health facilities.

Machakos’ proximity to urban Nairobi put it at risk to spread the virus. Gendo and her team prepared diligently to ensure that the hospital was well equipped and ready to provide critical care to COVID-19 patients, while still conducting other day-to-day operations. But the reality of the pandemic tested well-laid plans.

“There was a lot of confusion, there was a lot of stigma. People were scared,” Gendo said. “For me, I felt overwhelmed and angry, but I knew I just had to get it done.”

Overwhelmed, frustrated, tired, angry, and scared: These are some of the sentiments resonating among the medical professionals I spoke with. For Murgor it meant that for six months she could not tell her mother that she was working in the COVID-19 unit; she didn’t want to frighten her.

Gendo also felt the pressure. One of her responsibilities was managing a team of colleagues struggling with high blood pressure, stress, and depression from seeing and dealing with sick patients and an uncertain future.

“We must move as one humanity”

To deal with this unprecedented global medical crisis, this community of Kenyan doctors is finding ways to lean on each other and remain productive and positive throughout the emergency. They have WhatsApp groups to check up on those who are struggling, talk through the emotional and physical fatigue, and deliver meals to other medical colleagues on quarantine.

Now, with Kenya’s preparation for a roll-out of a COVID-19 vaccine, some feel more hopeful.

I spoke with Peter Okoth, a health specialist at UNICEF Kenya, who supports the Ministry of Health’s immunization program. UNICEF is leading the procurement and logistics for COVID-19 vaccines as part of the COVAX facility. This facility seeks to ensure that people living in developing countries like Kenya get a fair shot at recovery.

Peter Okoth, a Health Specialist at UNICEF Kenya.

Photo: Courtesy of UNICEF Kenya

Okoth is very familiar with what it takes to deliver an efficient vaccination campaign—this has been the focus of his career for more than 10 years. He has supported the government in establishing a deployment plan for the first batch of 24 million COVID-19 doses, targeting those vulnerable to the disease, including frontline workers. This vaccination rollout set for later in February will be a collaborative effort including public and private health facilities.

“The truth is that leaving behind any part of the country or any group of people is not going to help us sort out the impact of COVID in the country,” Okoth said. “We must move as one humanity… this will be a futile attempt.”

Upholding an oath

When I talked to my sister about how the pandemic has impacted how she views her medical career in Kenya, it is clear that she has had a year of deep reflection. Edith is currently doing her residency to eventually become a pediatrician. Though she hasn’t been working in a COVID-19 unit, she is prepared for the possibility—and she says all health workers are committed to fulfill their oath to humanity.

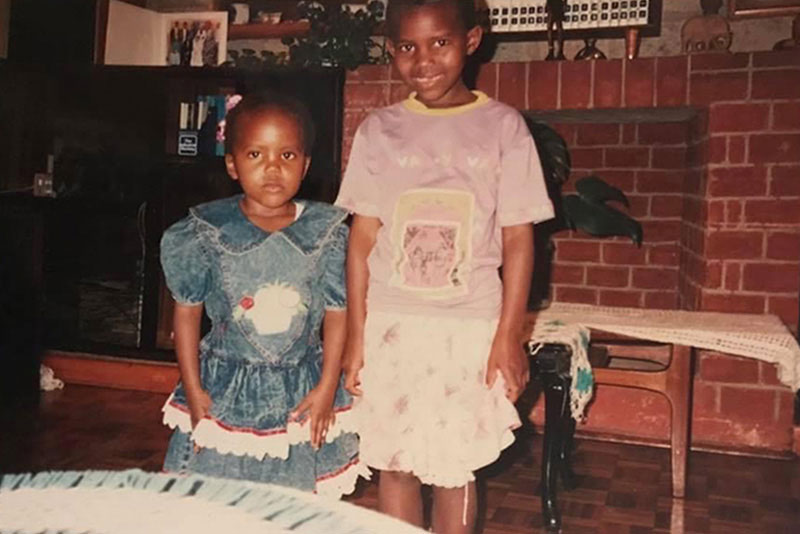

Daisy (right) and Edith Serem at their home in Nairobi, Kenya, in the early 1990s. Photo: Courtesy of the author

“I started to view our profession almost like that of a soldier,” she said. “You go into battle without any idea of the outcome, but you put yourself on the frontline and make sure you protect those behind you. The little sacrifice that you make goes a long way to make other people’s lives comfortable.”

Even as I worry about my sister’s possible exposure to the virus, and the exposure her colleagues are facing, I also am inspired by them. My sister is right—they are protecting us, and we must continue to do what we can to protect them by wearing masks, remaining socially distant, and avoiding any large gatherings.

Published in February 2021